ADHD & Working Memory Limits

Quick Answer:

ADHD often affects working memory by reducing how reliably information stays “online” while attention shifts. Instead of a stable mental workspace, working memory can become more vulnerable to distraction, interference, and rapid decay—especially during multi-step tasks. This can look like forgetting instructions mid-task, losing your place, or restarting repeatedly.

• How to improve working memory with exercises or training plans.

• “Working memory score” norms or digit-span benchmarks.

• Diagnosis, medication decisions, or individualized ADHD treatment.

• Clinical advice (this is an educational explanation).

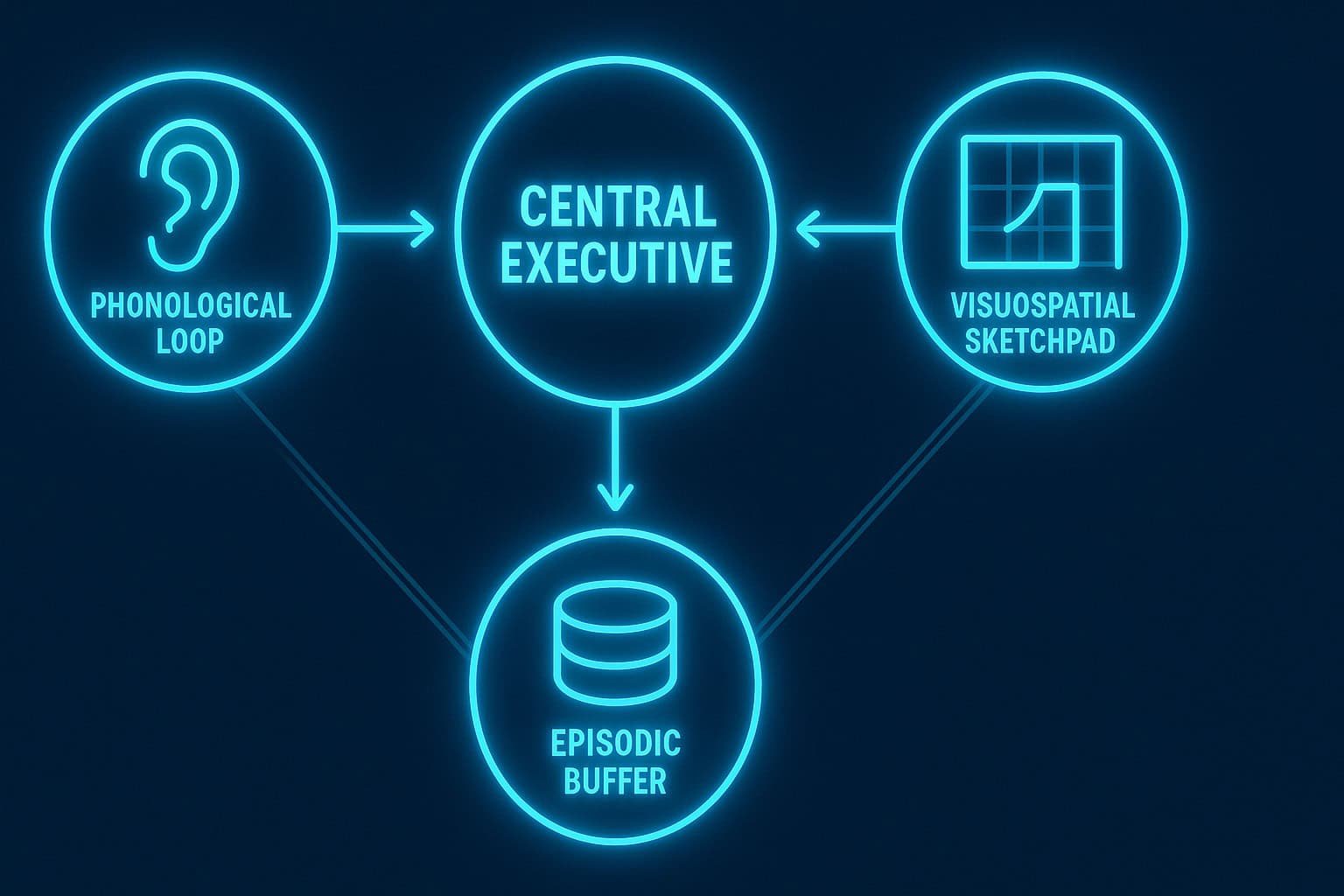

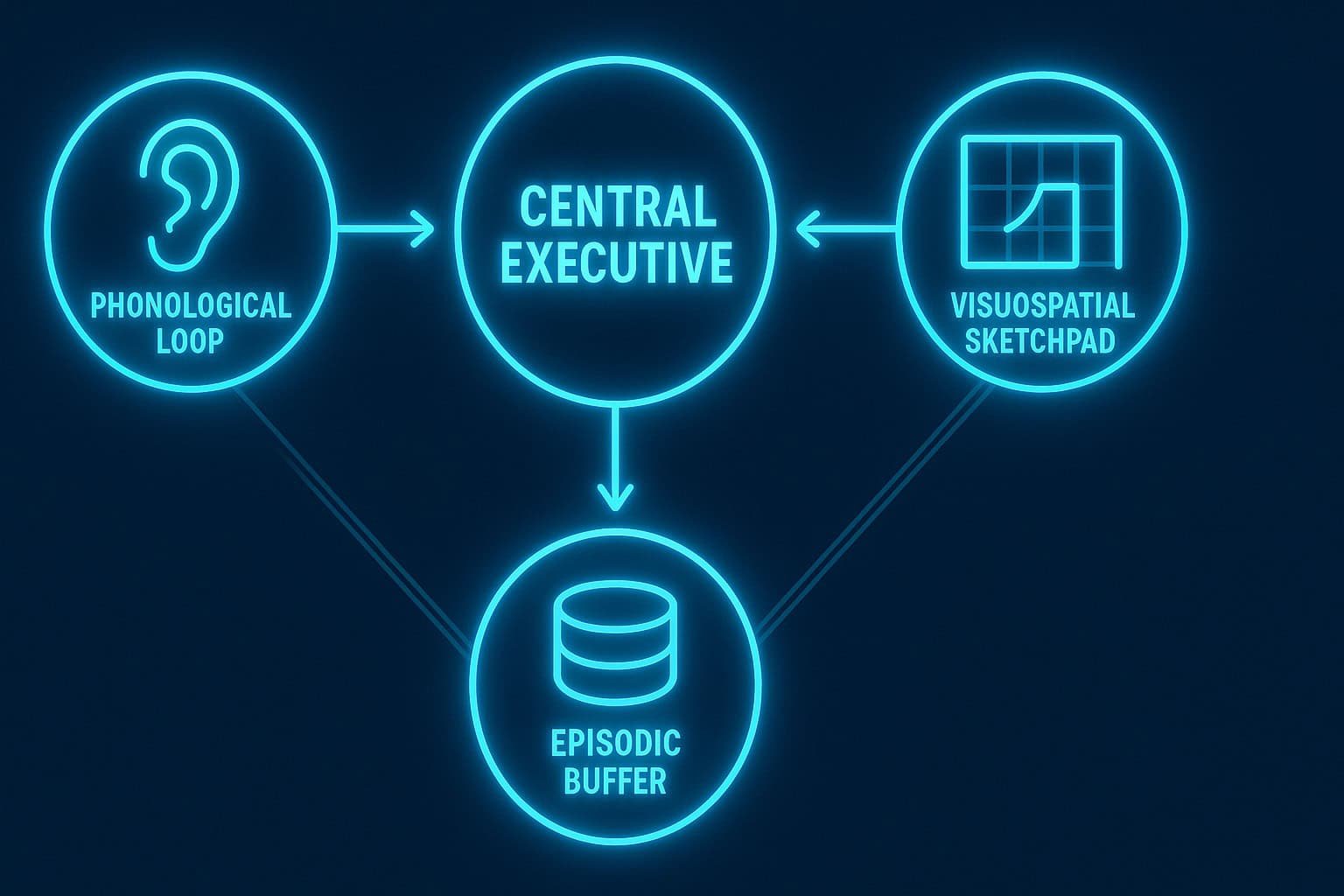

The Job of Working Memory in Everyday Tasks

Let’s break this down without the jargon. Think of your working memory as your brain’s active desk. It’s not just a notepad for a phone number. It’s the whole desk where you’re using that number to solve a problem, following a recipe step-by-step, or keeping track of who said what in a lively conversation. It’s where you update, shuffle, and actually work with the thoughts you’re holding in mind right now. When it’s running smoothly, you don’t even notice it. When it’s struggling, it feels like papers are constantly sliding off that desk.

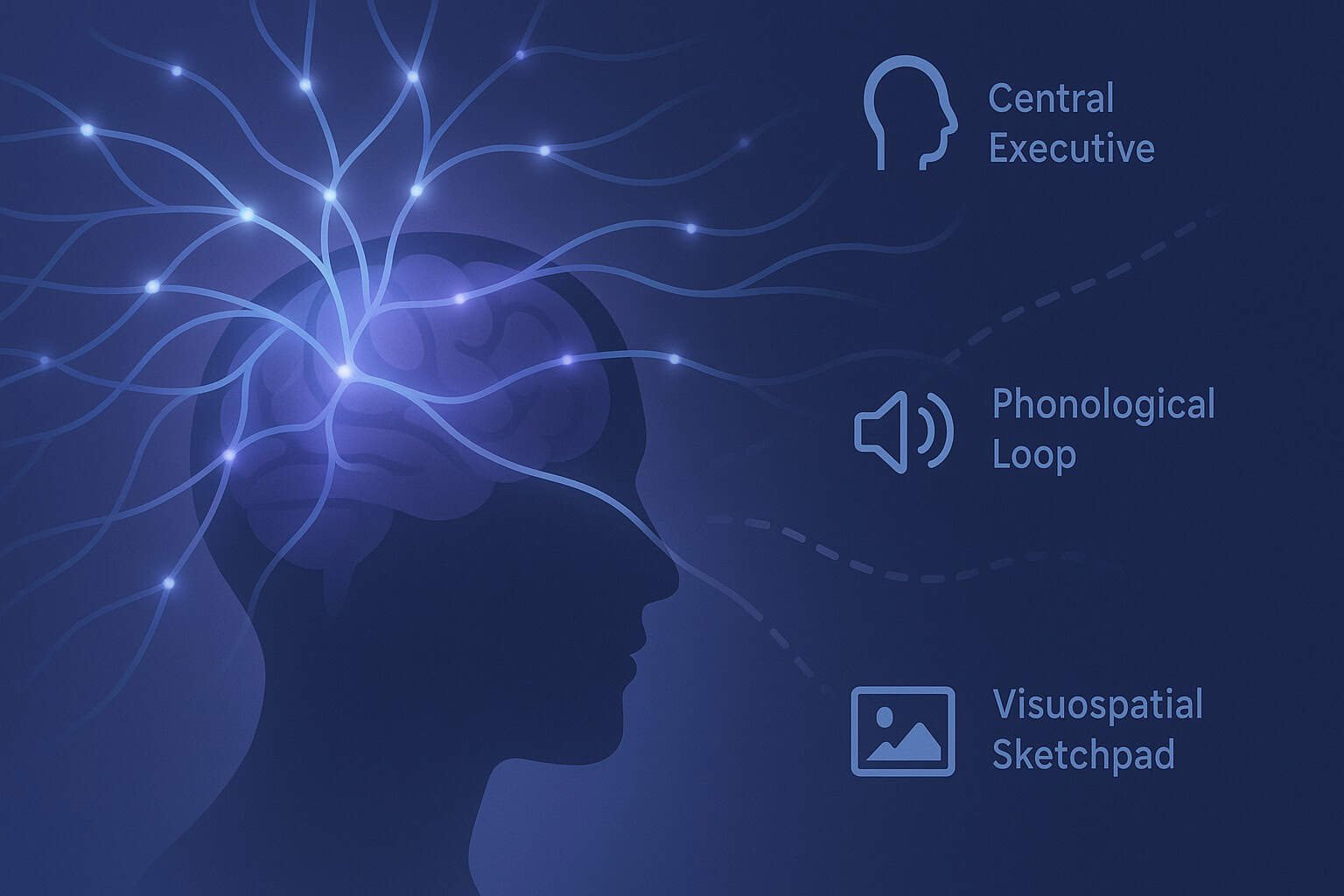

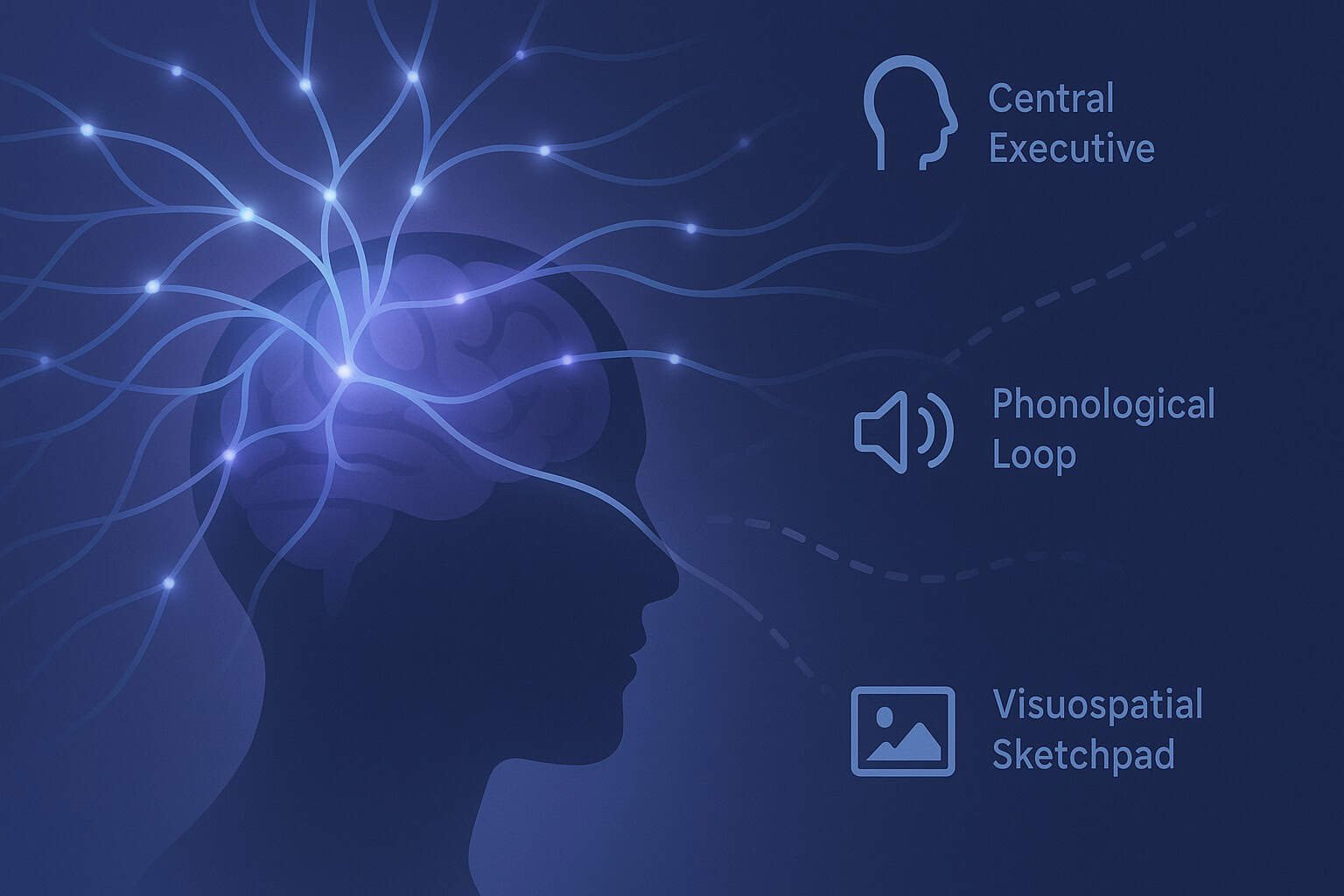

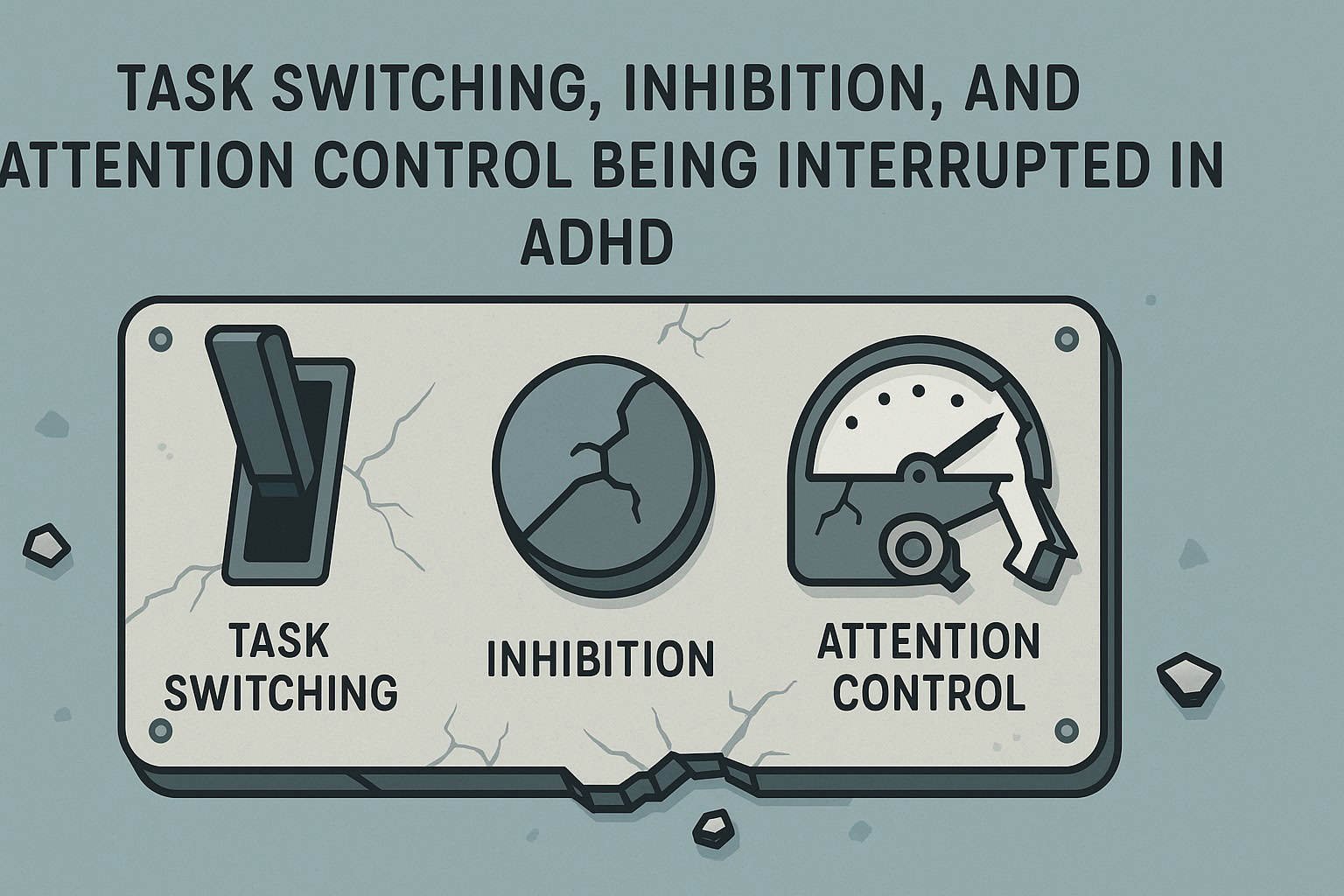

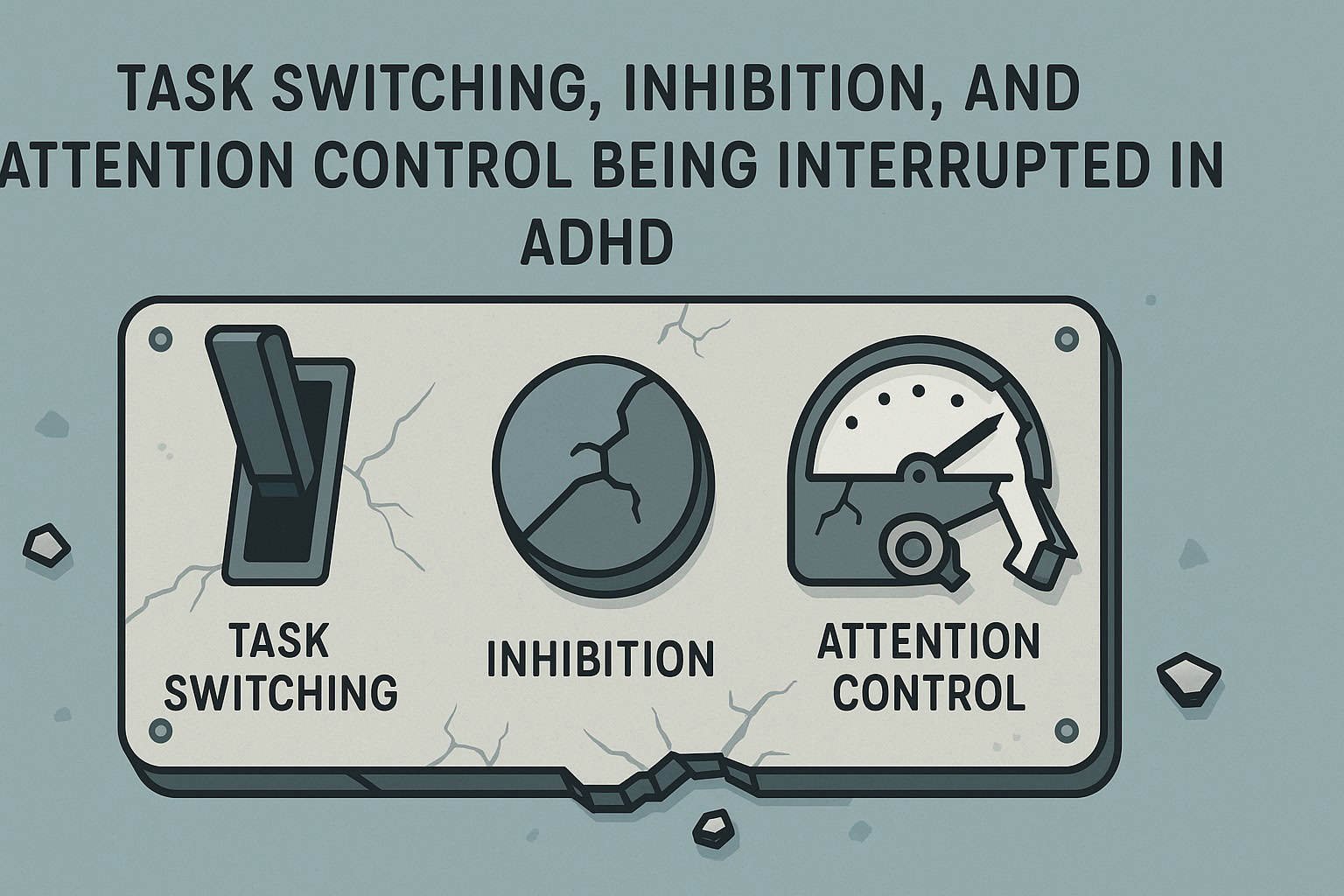

So, what’s actually different? It’s less about having a smaller desk and more about the desk being wobbly and in a windy room. Research, including a significant review in the National Library of Medicine, confirms that ADHD is linked to substantial challenges with the central executive part of working memory—the part that manages the workspace. Here are the three main things that happen:

- Heightened Interference Sensitivity: New information barges in and shoves the old stuff out. A text notification, a passing thought, or the next item on your to-do list can overwrite what you were just holding onto. It makes information feel like it has a super short “shelf life.”

- Costly Attention Shifts: Every tiny shift in focus has a tax. Look away for a second? The contents of your mental workspace can reset or fade. This is why switching between tasks feels so exhausting and ineffective.

- Maintenance Instability: Actively keeping information “lit up” and fresh in your mind takes a lot of conscious effort. Without that constant, effortful rehearsal, the mental signal just fades into the background noise.

This table shows the common differences in experience, focusing on how the process feels rather than on abstract scores.

| Aspect | Neurotypical Working Memory | ADHD Working Memory (Common Experience) |

|---|---|---|

| Stability | A relatively stable mental workspace. Information can be held with consistent, moderate effort. | A “fragile” workspace. Much more vulnerable to interference; info decays faster without active maintenance. |

| During Multi-Step Tasks | Can follow sequential steps while holding the initial goal in mind. | High risk of losing the thread. Later steps can overwrite earlier ones, causing restarts or skipped stages. |

| Under Distraction | Some ability to filter out noise and maintain the primary task. | Prone to hijacking. Distractions easily invade the workspace, pushing out what you were trying to focus on. |

| Retrieval for Use | Can usually access the information they were just holding on to. | Frequent “tip-of-the-tongue” moments or blanking, even for info processed seconds ago. |

Why Multi-Step Instructions Fall Apart: A Step-by-Step Flow

Let’s walk through a classic example. Someone says, “Grab the keys from the table, then take out the recycling, and on your way back, check the mail.” Here’s what often happens in the working memory system:

- Encode Step 1: “Grab keys” enters the working memory workspace. So far, so good.

- Execute & Shift Attention: You walk to the table. This physical action and change of scene pulls your attention.

- Interference & Decay: You see the mail on the table. This new, strong visual information enters your workspace. The original instruction (Step 2: “Take out recycling”) wasn’t being actively rehearsed at that moment and got compromised—either degraded or completely shoved out by the mail.

- Result: You come back with the keys and the mail, having completely forgotten the recycling. It’s not carelessness. It’s the instruction literally failing to survive the attention shift and the interference.

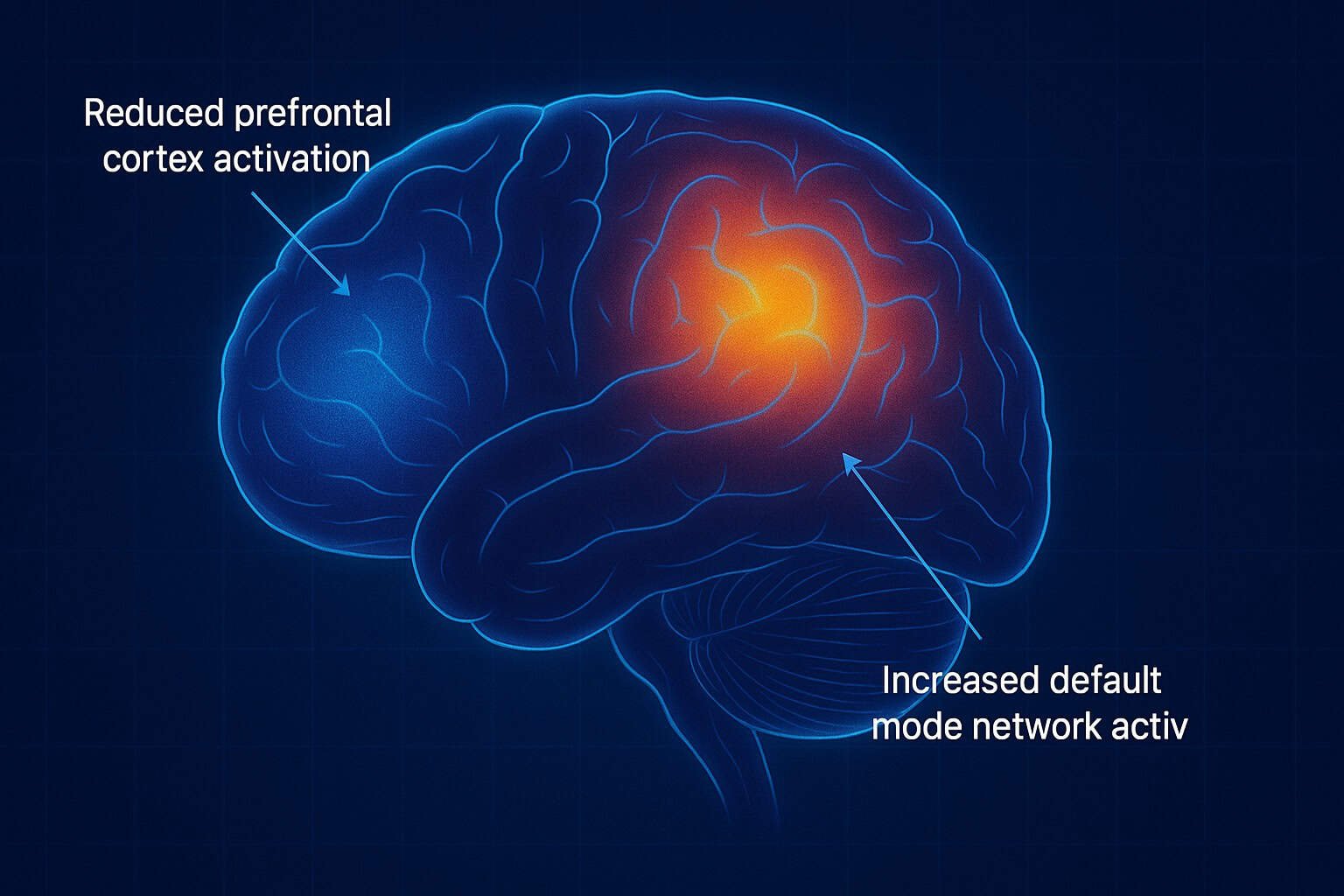

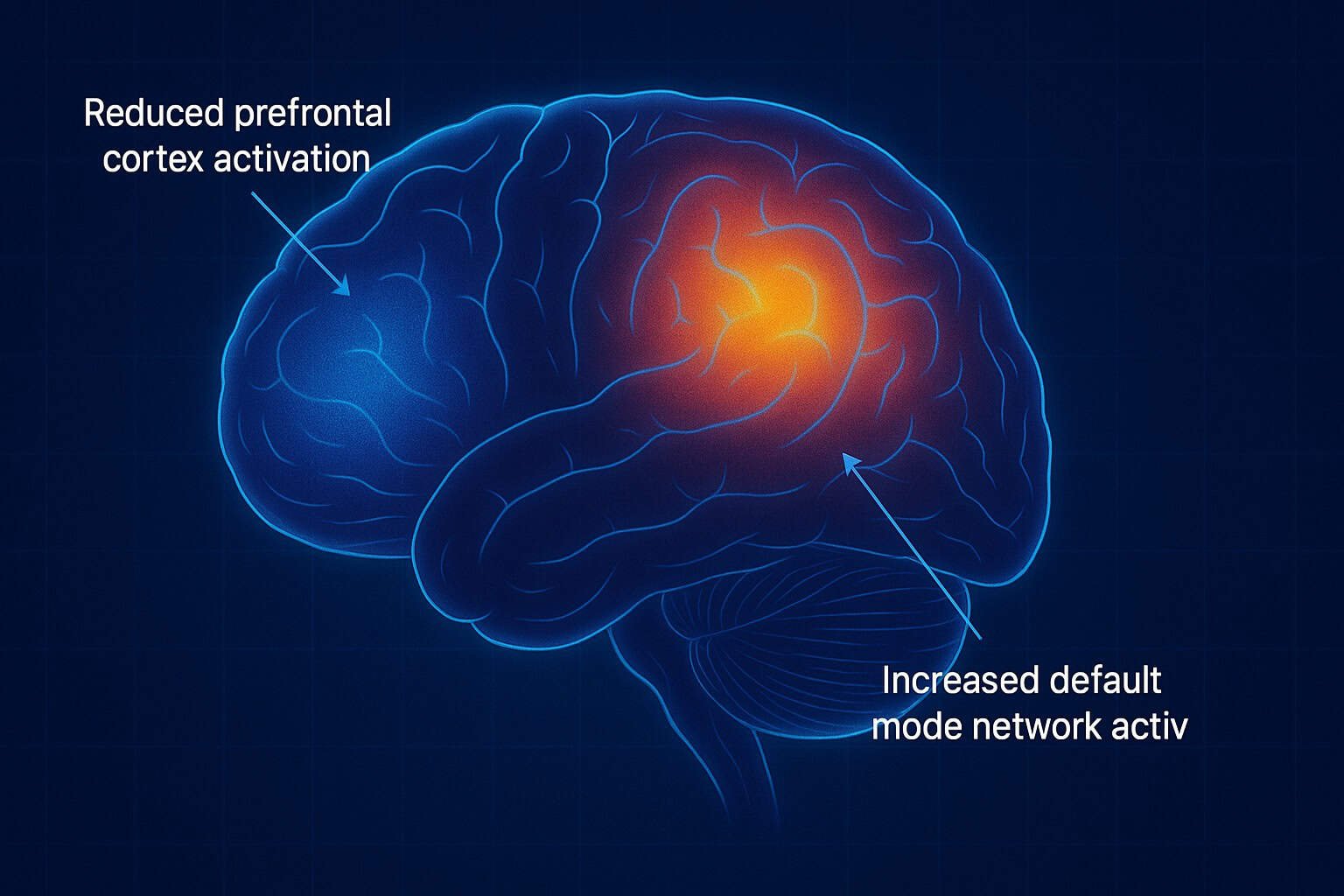

These experiences aren’t just “in your head” in the colloquial sense—they’re rooted in observable brain function. Studies using neuroimaging show specific differences.

Frontoparietal Control Networks

This network, especially the prefrontal cortex, is like the manager of your mental desk. It directs attention and maintains information. Research, such as a study linked in Scientific Reports, indicates that adults with ADHD can have decreased coordination (functional connectivity) in these very networks during working memory tasks. The manager’s communication system is a bit less efficient.

Dopamine Regulation

Dopamine isn’t just a “feel-good” chemical. It’s crucial for signaling what’s important and for stabilizing the circuits that hold information. Irregular dopamine function, which is common in ADHD, might disrupt the brain’s ability to learn the best strategies for managing that limited workspace efficiently.

Default Mode Intrusion

Your brain has a “default mode network” that’s active when your mind wanders. In ADHD, this network might compete more intrusively with the “executive” networks needed for focused tasks. It’s like having a loud radio playing in the background of your office, constantly pulling resources away from the work on your desk.

Explore More on MemoryRush

This article is part of MemoryRush’s structured framework for understanding cognition. To build on what you’ve learned here, explore these related pages:

For Practical Strategies

- Learn about frameworks and tools for support in our dedicated guide: ADHD Working Memory Strategies.

Core Foundation Concepts

- Build your foundation with the parent page: Working Memory Definition & Framework.

- Clarify a key distinction in working memory. Result: vs. short-term memory.

Touheed Ali

Touheed Ali is the founder and editor of MemoryRush, an educational cognitive science platform. He builds and maintains interactive tools focused on memory, attention, and reaction time.

His work centers on translating established cognitive science concepts into clear, accessible learning experiences, with an emphasis on transparency and responsible design.

MemoryRush

Educational Cognitive Science Platform • Memory • Attention • Reaction Time

Educational Use Only

MemoryRush is created for learning and self-exploration and does not provide medical, psychological, or clinical evaluation.

2 thoughts on “ADHD & Working Memory Limits: A Simple Neuroscience Breakdown”

Comments are closed.