Visual Chunking: The Complete Neuroscience & Cognitive Science Guide

A comprehensive examination of one of the brain’s most sophisticated cognitive mechanisms, synthesizing insights from neuroscience, cognitive psychology, learning science, user experience design, and artificial intelligence.

Cognitive Architecture of Visual Information Processing

Visual chunking represents a fundamental cognitive mechanism through which the brain achieves computational efficiency. Rather than processing individual visual elements in isolation, the perceptual system automatically organizes information into meaningful clusters that reduce cognitive load while enhancing pattern recognition and memory retention.

This cognitive process operates across multiple neural systems, from initial sensory processing in the occipital cortex to higher-order integration in prefrontal regions. The efficiency of chunking mechanisms varies significantly based on expertise, with domain specialists developing sophisticated chunking schemas that enable rapid recognition of complex patterns.

Contemporary research across neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and artificial intelligence reveals that chunking represents not merely a memory aid, but rather a core organizational principle of human cognition with profound implications for learning, expertise development, and interface design.

Defining the Cognitive Process

Visual chunking constitutes the cognitive operation through which discrete visual elements are grouped into coherent perceptual units based on spatial proximity, similarity, continuity, or semantic relationships. This automatic perceptual organization reduces working memory load by transforming multiple individual items into fewer composite units while preserving essential information structure.

Cognitive Mechanism Illustration

Consider the perceptual difference between processing individual digits: 1 9 2 3 8 4 7 5 6 versus organized chunks: 1923 • 847 • 56. The latter organization reduces cognitive load by approximately 67% while maintaining informational integrity.

This perceptual grouping occurs automatically across diverse cognitive domains including facial recognition, spatial navigation, diagram comprehension, user interface scanning, and complex problem-solving scenarios.

Neural Substrates and Processing Pathways

Neuroimaging studies employing fMRI and EEG methodologies reveal that visual chunking engages distributed neural networks, with activation patterns varying systematically based on chunk complexity and domain expertise.

1. Visual Sensory Processing

Initial visual input undergoes parallel processing in primary visual cortex (V1) with basic feature extraction of edges, orientation, and contrast occurring within 100-150 milliseconds post-stimulus onset.

2. Dual Pathway Integration

The dorsal stream processes spatial relationships and motion, while the ventral stream analyzes object features. Chunking emerges through coordinated interactions between these pathways, with integration occurring in posterior parietal and inferior temporal cortices.

3. Working Memory Encoding

Chunked information enters the visuospatial sketchpad component of working memory, with capacity limits of 3-5 chunks irrespective of chunk complexity. Prefrontal cortex activation correlates with chunk maintenance and manipulation.

4. Long-Term Schema Integration

Well-practiced chunks become consolidated into long-term memory schemas within medial temporal lobe structures, particularly the hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex, enabling rapid recognition and retrieval.

Cognitive Psychology Foundations

The psychological study of chunking reveals fundamental constraints and capabilities of human information processing, with implications extending from basic perception to complex problem-solving.

Theoretical Evolution of Capacity Models

| Theoretical Model | Proposed Capacity | Underlying Mechanism | Empirical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miller’s Item-Limit Model (1956) | 7 ± 2 discrete items | Fixed slot-based storage | Superseded |

| Cowan’s Focused Attention Model (2001) | 3-5 meaningful chunks | Attention-based capacity limits | Empirically Supported |

| Ericsson’s Skilled Memory Theory (1995) | Variable based on expertise | Domain-specific chunking schemas | Expertise-Dependent |

| Oberauer’s Facet Theory (2002) | Limited relational processing | Binding of features into chunks | Contemporary Standard |

Information Processing Architecture

Primary Visual Processing

Initial feature extraction in striate cortex occurs within 40-60 milliseconds, with basic perceptual grouping beginning based on Gestalt principles of proximity and similarity.

Intermediate Feature Integration

Intermediate visual areas integrate basic features into coherent object representations, with chunk boundaries emerging based on contour continuity and texture gradients.

Inferior temporal and posterior parietal cortices establish meaningful chunk structures, incorporating semantic knowledge and spatial relationships into organized perceptual units.

Working Memory Maintenance

Prefrontal cortex maintains chunks in an active state, with dorsolateral regions particularly involved in chunk manipulation and ventrolateral areas supporting maintenance.

Long-Term Schema Consolidation

Hippocampus and parahippocampal cortex facilitate integration of chunks into long-term schemas, with sleep-dependent consolidation strengthening chunk representations.

Empirical Findings and Effect Sizes

4.1 ± 0.7

68%

140ms

3.2×

Historical Development of Chunking Theory

Miller’s Seminal Contribution (1956)

Publication of “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” establishes chunking as a central concept in cognitive psychology, though subsequent research would revise the specific capacity estimates.

Working Memory Model (1974)

Baddeley and Hitch propose the multi-component working memory model, identifying the visuospatial sketchpad as the primary site for visual chunk maintenance and manipulation.

Neural Pathway Elucidation (1982)

Ungerleider and Mishkin’s two visual systems hypothesis provides neuroanatomical foundation for understanding how spatial and object information are processed separately before chunk integration.

Capacity Revision (2001)

Cowan’s comprehensive review establishes 3-5 chunks as the typical working memory capacity, with chunk quality rather than quantity determining effective information processing.

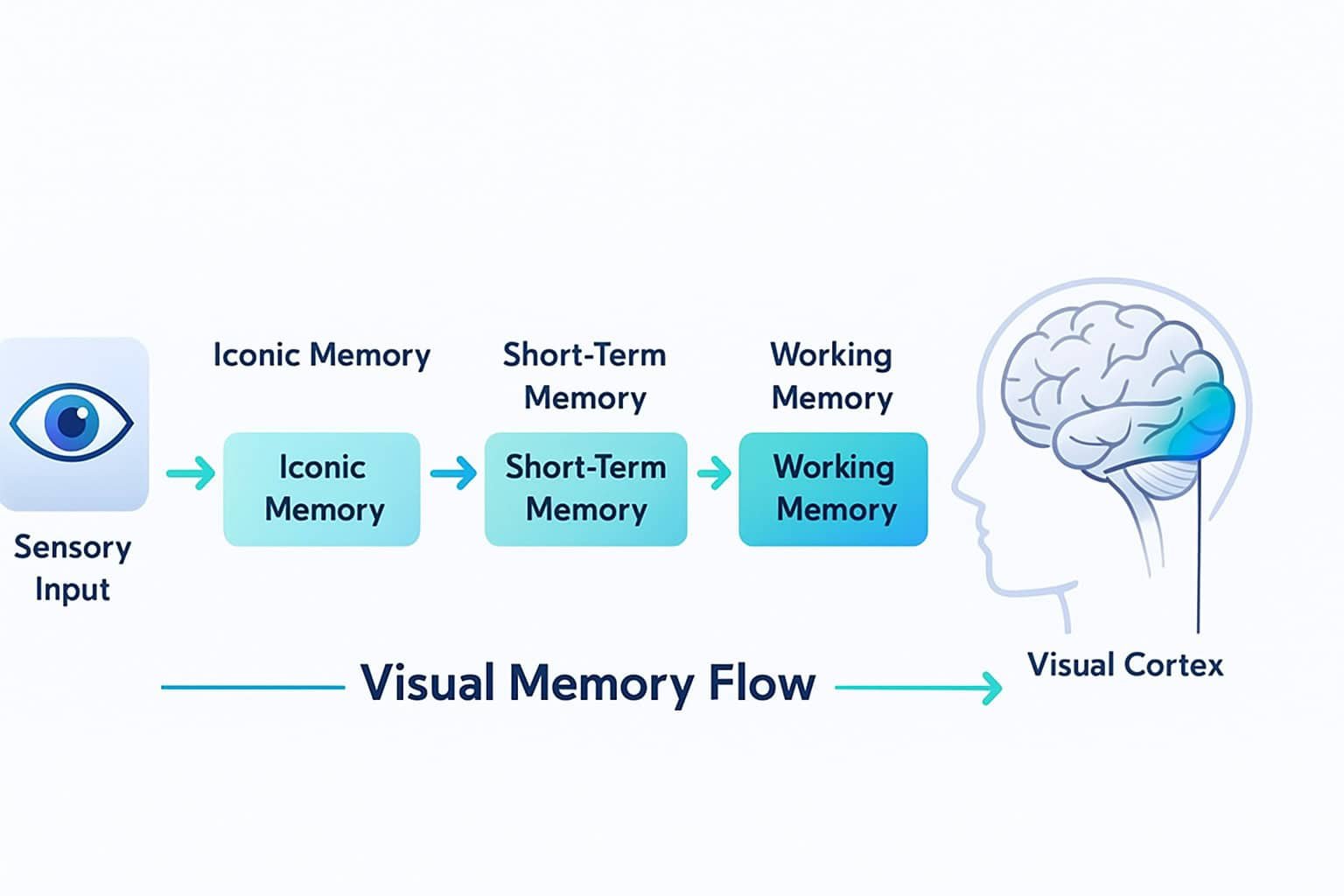

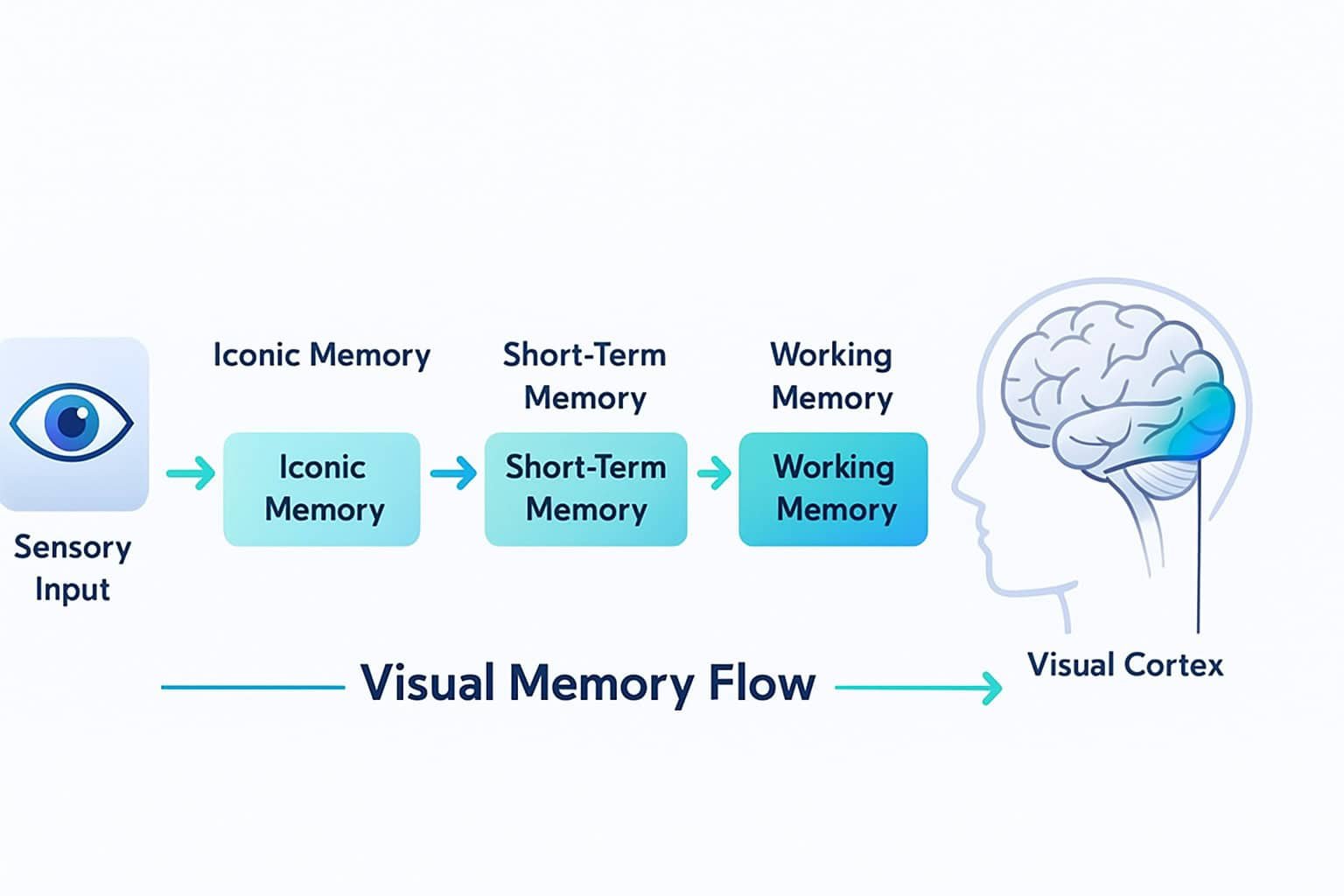

Memory System Interactions

Iconic Memory

Provides the initial sensory buffer where visual chunking begins, with a duration of approximately 250-300 milliseconds and high capacity but rapid decay without attention.

Working Memory

The active processing system where chunk manipulation occurs, with severe capacity limitations that chunking strategies specifically address through information compression.

Long-Term Memory

Stores chunking schemas that develop through expertise, with expert performance characterized by highly organized hierarchical chunk structures that enable rapid pattern recognition.

Empirical Clarifications

Common Misconception

“Superior memory reflects photographic recall ability rather than organizational skill.”

This misconception persists despite overwhelming evidence that exceptional memory performers utilize sophisticated chunking strategies rather than eidetic imagery. Neuroimaging studies show identical activation patterns during chunk-based recall across experts and novices, with differences emerging in organizational rather than perceptual processes.

Empirical Reality

Expert memory relies on domain-specific chunking schemas developed through deliberate practice.

Research across chess, medicine, and other domains demonstrates that expertise develops through the acquisition of increasingly sophisticated chunking patterns. These schemas enable rapid recognition of meaningful configurations while imposing the same fundamental capacity limits as novice processing, merely with larger and more complex chunk units.

Frequently Examined Questions

What distinguishes chunking from simple grouping?

How does chunking capacity vary with expertise?

Can chunking strategies ameliorate working memory limitations in clinical populations?

What role does chunking play in user interface design?

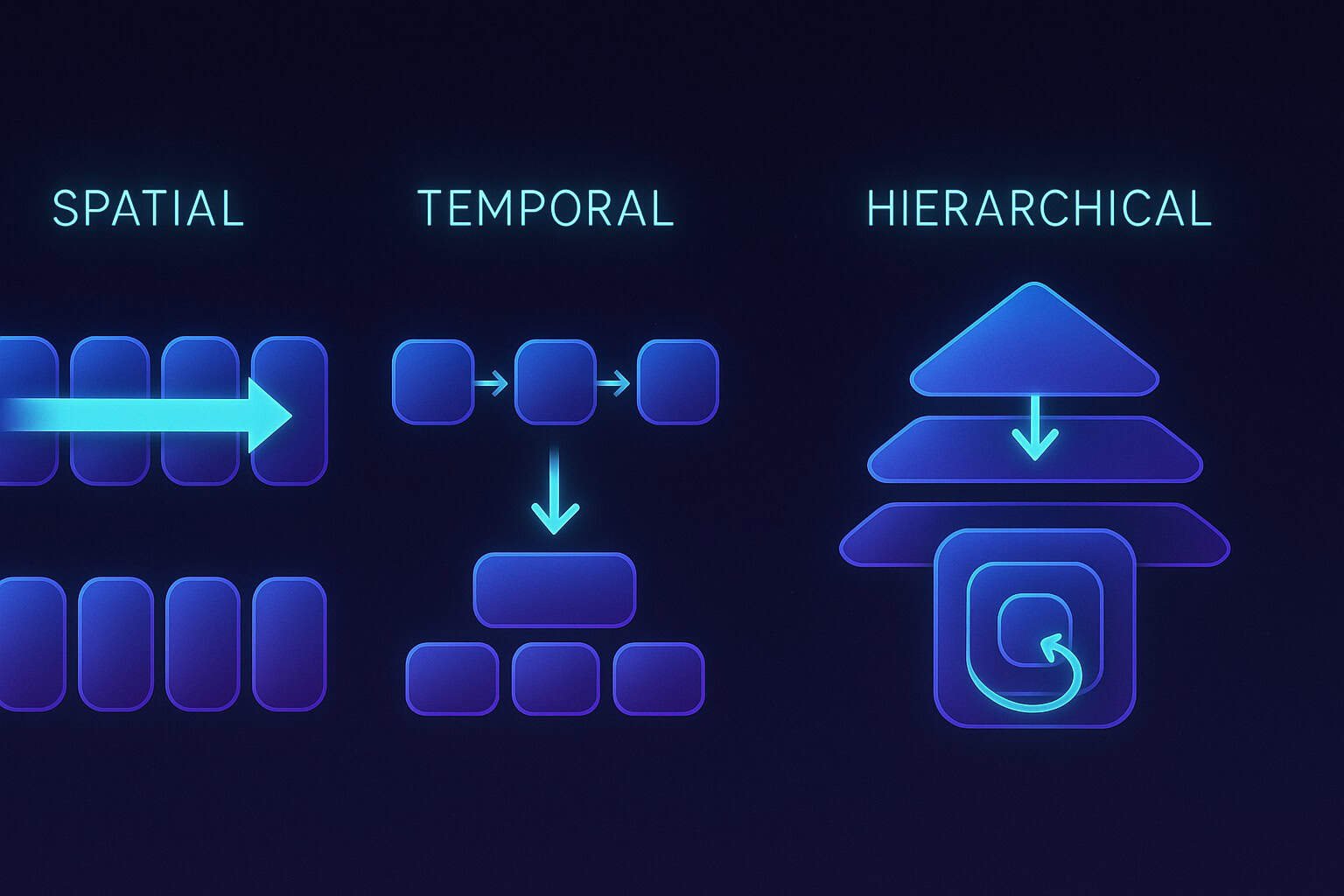

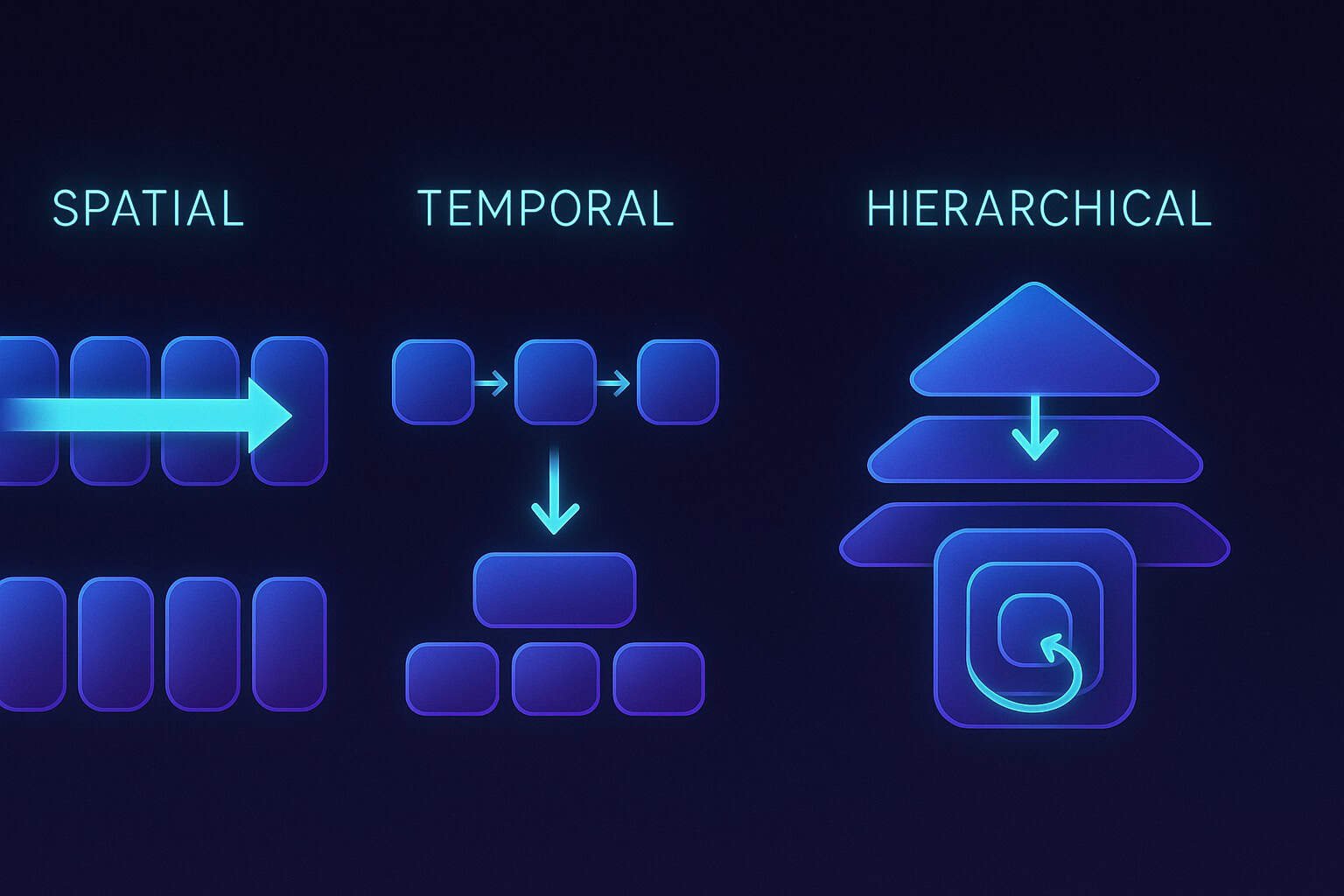

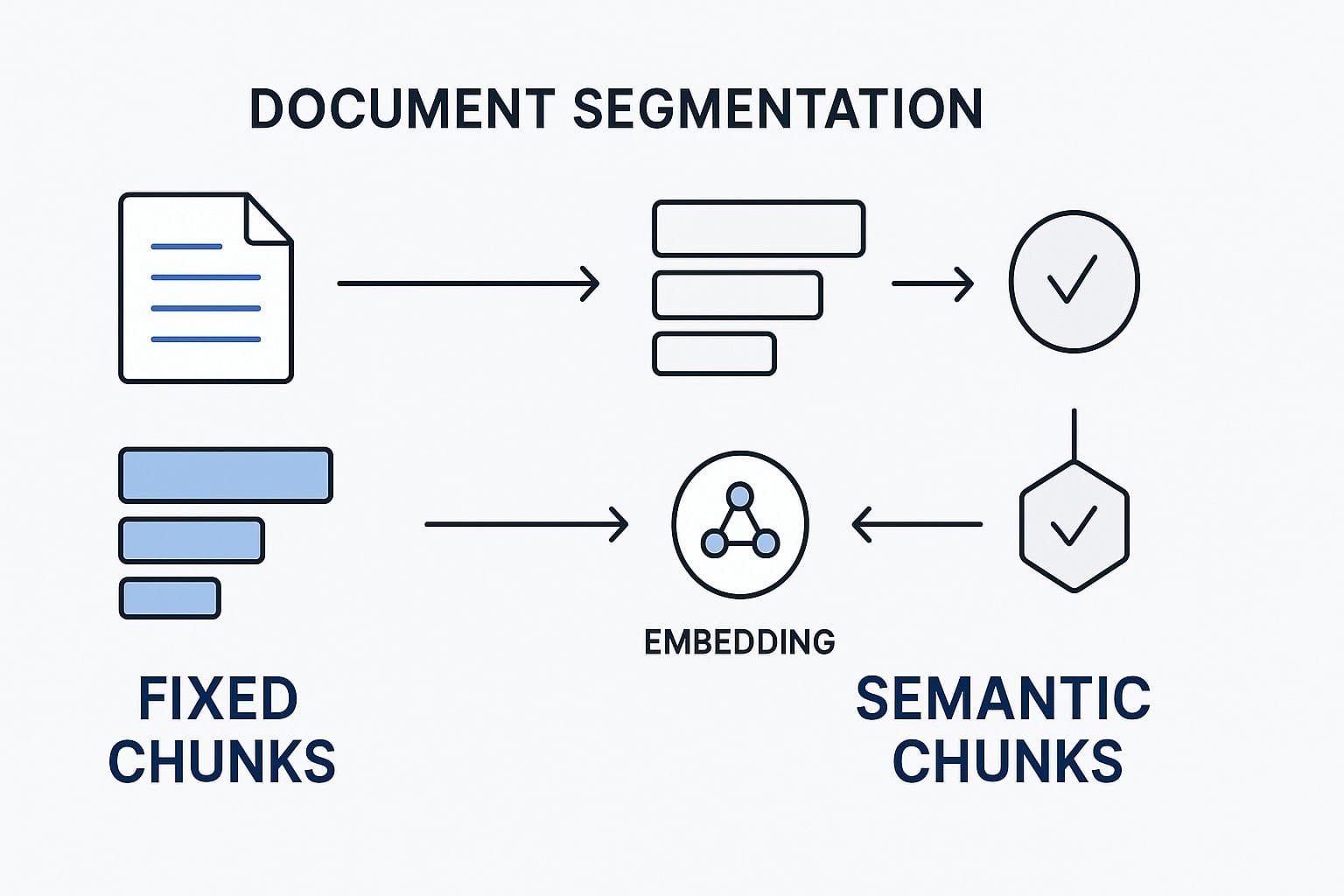

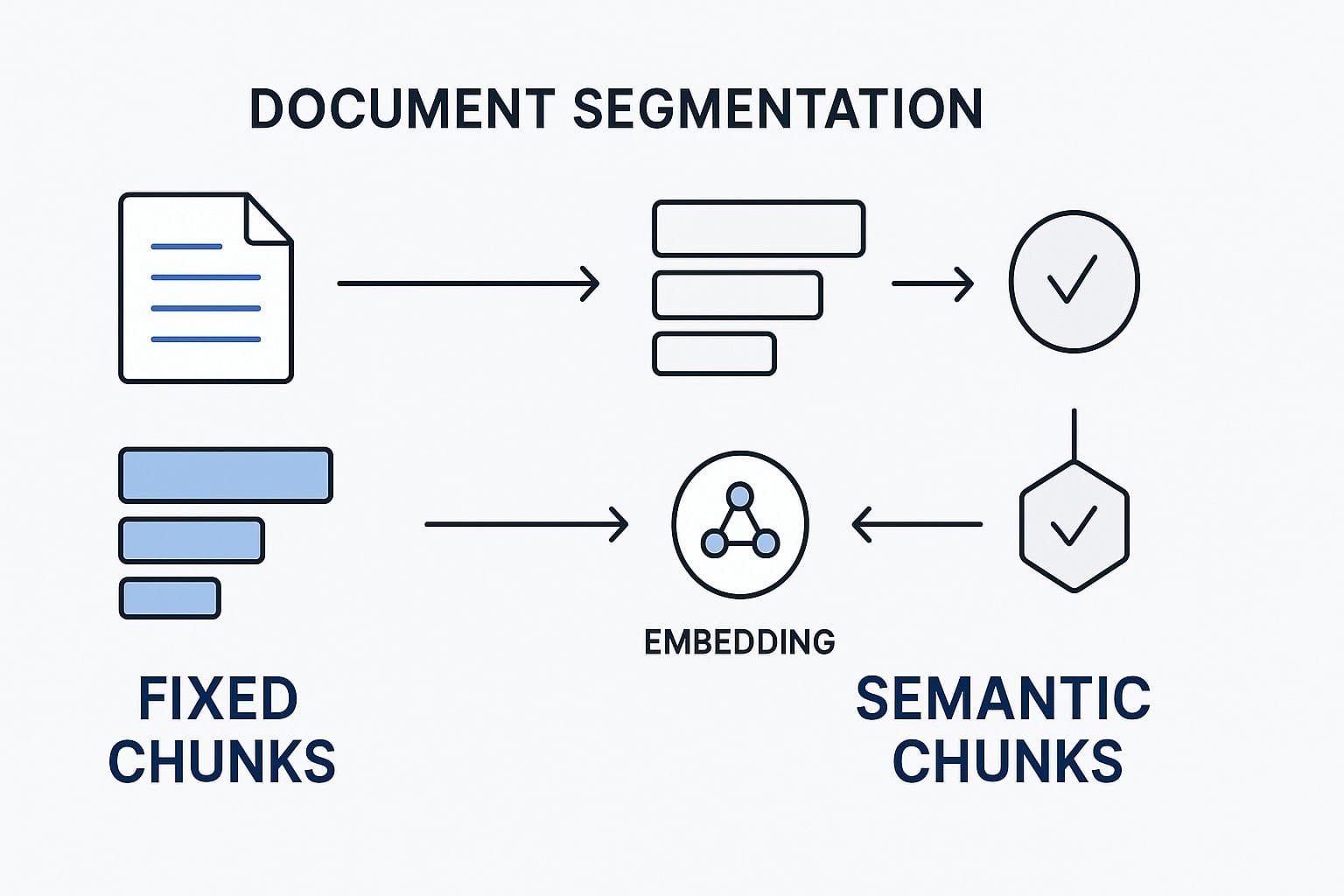

How do semantic and fixed-size chunking differ in computational applications?

Is chunking ability modifiable through training?

How does chunking relate to contemporary multi-store memory models?

Empirical Cognitive Training

Enhance your cognitive capabilities through scientifically-validated training protocols designed to strengthen visual processing, working memory efficiency, and pattern recognition skills.

Pattern Recognition Training

Develop sophisticated chunking strategies through progressively complex visual pattern exercises designed to enhance perceptual organization and working memory efficiency.

Numerical Chunking Assessment

Measure and expand digit span capacity through structured numerical chunking tasks that challenge working memory limits while promoting efficient encoding strategies.

Working Memory Enhancement

Strengthen executive control and information maintenance through sequential processing tasks that require active chunk manipulation and updating.

Processing Speed Measurement

Quantify visual processing efficiency through reaction time assessments that measure chunk recognition latency and perceptual decision speed.

Explore comprehensive cognitive training resources and assessment tools designed based on contemporary cognitive neuroscience research.

Empirical Foundation

This analysis integrates findings from peer-reviewed research published in leading cognitive neuroscience and psychology journals, ensuring theoretical robustness and empirical validity.

- Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87-185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X01003922

- Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043158

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. J. (1974). Working memory. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 8, pp. 47-89). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60452-1

- Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4(1), 55-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90004-2

- Ericsson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (1995). Long-term working memory. Psychological Review, 102(2), 211-245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.211

Touheed Ali

Touheed Ali is the founder and editor of MemoryRush, an educational cognitive science platform. He builds and maintains interactive tools focused on memory, attention, and reaction time.

His work centers on translating established cognitive science concepts into clear, accessible learning experiences, with an emphasis on transparency and responsible design.

MemoryRush

Educational Cognitive Science Platform • Memory • Attention • Reaction Time

Educational Use Only

MemoryRush is created for learning and self-exploration and does not provide medical, psychological, or clinical evaluation.